Yes, this is a column about the columns that builders in Bennington used before 1860. There were many, most of them fluted.

This is the Charles Cooper Residence.

Below it is the home, and probably the office, of Dr. Goodall.

Both have 2 story tall porticoes with dramatic Doric columns.

These houses were photographed in 1904 for the Bennington Souvenir. Both date from the 1850's and were on Main Street. The Cooper Residence was extensively updated in the 1880's as can be seen by the curved roof over the veranda that nestles between the wings of the house.

Both were, in 1904, painted several colors, no longer the classic white preferred in the 1850's.

The first house is gone, the second one also. I show them as examples of the many Bennington houses which had dramatic columns.

Here is Bennington's Town Offices, built in 1842 for the Root family, given to Bennington in the 1920's to be the Town's offices.

For more about the Root House, see: https://passingbyjgr.blogspot.com/2020/11/benningtons-town-offices-originally.html

It also has Doric columns; columns with flutes, no base at the bottom and simple capitals at the top: classic American Greek Revival.

If you cut one in half it would look like this:

Long wooden shafts, 2" thick minimum, with their sides cut at angles so that when they are set side by side they join in a circle.* After three flutes are carved in each shaft, they are glued together on the edges and the inside with angled blocks and hide glue.

In 1842 this was new. As recently as 1836, when the Norton-Fenton House on Pleasant Street was built, the columns had been made from full trees, cut, shaped, and smoothed, with added capitals and bases.

The columns in the Old First Church, built in 1805, are also trees. Local tall, straight white pines. debarked and shaped, support the balcony, the ceiling of the meeting house, and

the roof as part of the attic trusses.

The next time you visit the church check the columns. You can see where tree branches were lopped off when the columns were shaped, and where the young men who sat in the balcony carved into those trees during church services.

Why did this change? Supply and technology.

The supply of tall straight trees close to the major seaport cities had dwindled. As early as 1820, the trees for the timber frames of houses along the seacoast north of Boston were being hauled by oxen and rafted down rivers from forests 50 miles away. Remember that in 1840, a 3 mile journey to town in a wagon took 45 minutes. Bringing the lumber to the cities cost money and time. Those logs was too precious to use whole.

At the same time the technology of saw mills had greatly improved. Saws could cut not just one board from a tree, but many boards at once.

Bennington still had the trees. It wanted the newest style: Greek Revival. The pattern books written by master builders and architects had plates and descriptions, including how to build the new fluted columns.

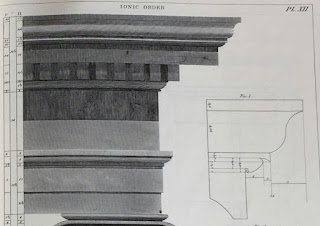

Asher Benjamin in his book,

The Architect,

or Practical House Carpenter, showed a Doric column with its base and capital. He included the proper proportions on the left and the profile on the right.

Benjamin accompanied his drawings with detailed instructions to the carpenter.* He wrote:

I especially like his explanation of the necessity of accuracy and 'exactness' in order to keep the work from being 'bad'.

Doric Columns, some much larger than those on the Town Offices, were used on Main Street, Pleasant Street and West Road, on Prospect Street in North Bennington. Those at Powers Market were brick, specially formed for that purpose.

*The image of the Doric column is part of Plate IV, titled: 'DORIC ORDER From the Temple of Theses in Athens'.

*The image of the cross section is half of Plate XXIV, titled 'Glueing up of Columns'. *The excerpt is from Page 52: PLATE XXIV To glue up the Shaft of a Column.

All are in The Architect, or Practical House Carpenter, by Asher Benjamin. 1830; reprint by Dover Publications.

Hiram Waters, a master builder whose shop was on Monument Avenue, Bennington, owned a copy of this book. It is possible that he was the carpenter for these houses.

For more on Hiram Waters, see https://passingbyjgr.blogspot.com/2020/10/hiram-waters-workshop-monument-avenue.html

See also issues of the Walloomsack Review, published by the Bennington Museum.